I spent the first part of my afternoon doing some online research on nearby religious groups, especially in Eastern traditions (Hinduisum, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, Daoism). I didn't really have much luck with Daoism, although I did find a local "Taoist Tai Chi" place--I'm not sure if it would count as a religious-studies oriented activity to visit there. I also found out some info on the local Chinese community, but as far as I could tell, this is to a large degree centered around a Chinese Missionary Alliance Church, so while their cultural activities would doubtless by enriching and educational, I'm not sure it would be that helpful for my purposes in finding places to require my World Religions students to visit in the Spring.

Hinduism was easy--I knew that there was a temple locally, and found its website with a good deal of information, including the name and e-mail address of the priest and the hours of operation. There is more than one Zen/other Buddhist meditation group in the area, as well. No Sikh groups in Toledo that I found, although I did find an address and phone number for a group of Jains.

A couple of interesting general resource sites: this is a directory of Buddhist groups in Ohio; and this is the site of Harvard's "The Pluralism Project", which allows me to search the state for various religious traditions (not Jews or Christians).

Elsewhere in the state, probably within driving distance, there are several different kinds of Buddhist that I found on that first site: Pure Land, Therevada, Tibetan. This is a really interesting part of the world to be studying World Religions in.

On the Western side, there are lots of kinds of Orthodox, Eastern Rite, and of course American Catholic and Protestant churches in Toledo. And we have three synagogues--an Orthodox, a Conservative, and a Reform congregation. There's a large Mosque here, too. To find Baha'i I would have to go farther, like to Dayton or Cincinnati. No luck with Zoroastrians.

I'm thinking I should plan to make some visits myself, before the semester begins, or at least some phone calls and e-mails to make contact with some of these communities in order to open the door a little before my students go.

Anyway, the opportunities are exciting.

------

"He Himself is our Peace." (Eph 2)

Monday, November 26, 2007

Local World Religions

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

random amusement

Sarah got a recruitment flyer in the mail today from the U.S. Navy. It offered her x amount of dollars for school together with an opportunity to become a navy officer. I found this amusing on more than one level.

We decided that the U.S. Armed Services should be required to offer equal amounts of student financial support to C.O.'s who do C.O. service (or who sit in jail if the government would prefer us to do that). This would be a great way to work against the poverty draft.

------

"He Himself is our Peace." (Eph 2)

Friday, November 16, 2007

Celebrations!!!

I just talked to the dept. chair, and I learned that I will be teaching Intro to Philosophy and World Religions next semester!!!!!!!!!!!!!

The (slight) downside to this is that it means two new preps while I'm still scrambling to finish up my degree. I'm not sure whether prepping for these lecture courses or for Logic will be more time consuming.

Oh, and I get to choose my own textbooks! :) I'll probably need to do this over Thanksgiving break, as the bookstore will need to know what books to order.

I'll have a very busy Christmas break!!

Please pray for me as I work out how to manage my time between teaching and the thesis, both over break and during the next semester. I *really* want to finish this Spring (as opposed to summer term), which means I *really* want to meet certain (hefty) writing goals in the next week or three. And I'm really good at procrastinating...and at prioritizing teaching prep over research & writing.

------

"He Himself is our Peace." (Eph 2)

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Between Pacifism and Jihad, IVP 2005

And now for something completely different…

So I got Dr. Charles’ new book via OhioLink today…and my initial reaction to it, I am somewhat ashamed to say, is violent anger. J Disclaimer: there might be some ranting in the following! These are my thoughts/initial reactions as I just begin to read the book (I really haven’t got far yet. It may be illuminating to compare these thoughts to my reflections further along, when I can read more of his arguments. That’s really why I’m publishing these comments.)

Let it not be thought that only Christians who admit the use of violence are engaging in responsible moral and theological reflection or responsible conversation with secular policy-makers. I trust Dr. Charles does not really think this is the case, but one might be led to think otherwise by his consistent criticism of Christians who do not think through moral issues and who do not engage with current events relevant to public policy on a national or global scale, combined with his holding up of (nigh exclusively) JWT proponents such as himself, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Paul Ramsey as models of Christians who are thinking and engaging the world responsibly, ethically, and Christianly.At times his rhetoric seems emotionally colored and strongly biased against the perspective of Christian nonviolence. He considers the response of some Christians to the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks of “Let us remember to forgive our enemies” to be a “theologically vacuous excess” that “will contribute little to civil society”. (11)

I hope that Dr. Charles will eventually engage with his opponents on the pacifist side with some exegetical depth (admittedly I am only in the first chapter). I want to know his reasons for rejecting the arguments of Yoder and Hauerwas and the like, and not just his reasons for embracing JWT.I appreciate the fact that Dr. Charles grew up Mennonite, and that his father was a CO in World War II. It increases my level of respect for him that he is not just arguing for a view that he has always been comfortable with, and was raised into. But I worry a little–perhaps unfoundedly–that he tends to characterize the Anabaptist perspective too monolithically, as advocating withdrawal from society. Not all Anabaptists, and not all Christian pacifists would do so. I have to admit that Dr. Charles’ political perspective is quite different from my own. He rejects what he calls “the self-righteous attitude of ‘America as empire’…attributing to our nation imperial or imperialistic designs that are reputedly causing the ills of the whole world.” (16). He is certainly right that self-righteousness should be no part of this attitude for Americans, but I really do perceive the US government’s policies over the last several decades to be imperialistic–even openly and unashamedly so at times. Dr. Charles argues against those who claim that JWT and pacifism share a common presumption against violence. The presumption, he says, is against injustice. JWT recognizes that peace is not merely the absence of conflict, and that there is something wrong–to be corrected–when a society is not justly ordered. I think he is right that “absence of conflict” is not the highest good–but that does not mean that war is an effective or just method of bringing about a just ordering of a society. Not only does war often fail (as in the present case!) to bring about a just ordering of society effectively, but even if it were to achieve this ideal result, the means taken are most decidedly unjust. In my view, the consistent, respectable pacifist position calls for (and to some extent participates in) nonviolent responses to injustice, both domestically and internationally. “When we speak of just war, we do not mean a war that, narrowly speaking, is just. Rather, we refer to warfare undertaken that is in conformity with the demands of charity, justice and human dignity, and that seeks to protect the innocent third party from gross injustice and social evil. These are the fundamental assumptions of just-war thinking.” (20). I applaud these words. I question the possibility of a war (especially a modern war conducted by the U.S. military!) which can meet these standards, not only as an ideal that forms a part of our leader’s political rhetoric, but as a lived reality, day to day, for the people on the front lines. Just how are you supposed to drop bombs in a way that is charitable, respectful of human dignity, and protects the innocent third party? This sounds to my ears like suggesting that we give someone a lethal injection while at the same time being motivated by an overriding concern for the condemned’s well-being! Dr. Charles speaks dismissively of the attitude of churches in the Cold War years who argued that “War could not possibly be justified … regardless of the gulf between democratic self-government and totalitarianism. Both superpowers…are immoral in ‘threatening’ the world.” (18) He is not really making an argument here, and I don’t suppose he is trying to at this point in the book. But it should still be said that one’s ordering of domestic society being more just does not justify an unjust war against another society (or its oppressed civilians! MAD is all about threatening noncombatant life!!). This is like saying that because our religion is better than someone else’s that we have a right to invade their territory and forcibly convert them. (This is, in fact, in political terms, what the White House’s explicit policy seems to be!). This smacks of cultural imperialism, if not any other kind of imperialism.

"He Himself is our Peace." (Eph 2)

Politics of Jesus: Reflections I (of ?)

Reflections on

The Politics of Jesus

by John Howard Yoder

I

1. Christocentric Ethics: The Normativity of Jesus in the Gospels

(from ch. 1, “The Possibility of a Messianic Ethic”)

At a popular level many Christians appeal to Jesus as a model for life and for right action. When I was a teenager (what seems like a very few short years ago), Christian teenagers were being taught (by the advertising media of the subculture, which of course infiltrated our church youth groups) to ask “What Would Jesus Do?”. (Incidentally, I have sometimes wondered: Would Jesus buy and wear WWJD bracelets and jewelry?) But how much direct help does scripture give us in answering that question? Does the New Testament present us with a substantive notion of what Jesus would do, based upon which we can do Christian normative ethics, or do Christian ethicists need to look elsewhere (i.e., in natural rather than special revelation) for our ethical foundations?

Yoder advances the hypothesis that the New Testament (read in the light of the Hebrew scriptural tradition that shaped its authors & audiences--Yoder is no proponent of the Marcionite heresy) does in fact give us a platform for social ethics. (The term “politics” in the title of the book is not meant to suggest that Jesus wants his disciples to take an active part in secular institutions of government; the term has a broader application to how his disciples are to live and act as members of society.) The project of The Politics of Jesus is to dig up confirming evidence for this hypothesis in the theology of the canonical New Testament writings. (Yoder does not consider himself qualified to attempt historical reconstructions of Jesus and his teachings that go behind the texts as we have them today; he comments more than once in a footnote, however, that the evidence in the canonical texts suggests that any such reconstruction would only strengthen the case for his hypothesis).

In his first chapter, Yoder surveys some arguments, common among Christian scholarship, for the thesis that Jesus and his teachings in the Gospels do not provide substantive normative answers for Christians’ questions in social ethics. Proponents of this thesis argue that Christians need to look elsewhere for answers to ethical questions; Yoder refers to these as “natural law” ethicists, broadly speaking. Here are some of the arguments of Yoder’s opponents: [note: my summary below does not exhaust Yoder’s presentation at this point of his argument]

1. Jesus gives only an interim ethic

Since Jesus expected the end of the present age to come soon, his ethical teachings became more and more irrelevant as the Church came to terms with the delay of the parousia. “Thus at any point where social ethics must deal with problems of duration, Jesus quite clearly can be of no help. If the impermanence of the social order is an axiom underlying the ethic of Jesus, then obviously the survival of this order for centuries ahs already invalidated the axiom.” (16)

2. Jesus gives only a personal (i.e., non-public) ethics

Jesus’ ethical teachings were intended to apply only to interpersonal relationships, not to social problems of a large scale. “His radical personalization of all ethical problems is only possible in a village sociology where knowing everyone and having time to treat everyone as a person is culturally an available possibility. … There is thus in the ethic of Jesus no intention to speak substantially to the problems of complex organization, of institutions and offices, cliques and power and crowds.” (16-17)

3. Jesus gives only an ethic for the powerless minority

Christians have ascended to positions of power in society (e.g., economic and political power). But “Jesus and his early followers lived in a world over which they had no control.” Christians in positions of power must look elsewhere for moral guidance in making the kinds of decisions they have the responsibility to make. “…the Christian is [today] obligated to answer questions which Jesus did not face. The individual Christian, or all Christians together, must accept responsibilities that were inconceivable in Jesus’ situation.” (17)

4. Jesus gives only spiritual (not social or ethical) teachings

Everything Jesus taught must be interpreted in light of the gospel of personal salvation. The point of his ethical teachings was not our obedience, but some spiritual aim, such as a recognition of our need for grace. The point of his life was not his ethical teachings, and we should not take his behavior with respect to social authorities as a model for our own, because Jesus’ life had the unique purpose of ending with a vicarious sacrificial atonement. The primary concern of the Christian life is not being ethical, but trusting in grace alone for our salvation. “For Roman Catholics this act of justification may be found to be in correlation with the sacraments, and for Protestants with one’s self-understanding, in response to the proclaimed Word; but never shall it be correlated with ethics.” (19)

Reflection #1

Response to (1):

(a) Perhaps to be faithful to the teachings of our Lord, we should continue to live as if the end of the present age is imminent. Perhaps we should not make our choices based on the assumption that the money we put in the stock market today will be there for our retirement in thirty or forty years. Perhaps we should give up all our allegiances to earthly institutions, knowing that they will not last.

(b) Perhaps the end of the age did come in Jesus’ lifetime, or immediately following his death & resurrection. Perhaps his ethics were not for the short span of his life only, but for the new age in which we presently live. Again, perhaps we should abandon all allegiances to the institutions of the old age.

(c) Remember that if there was a development in the theology of the early Church, during the writing of the New Testament books, toward accommodating the delay of the parousia, Jesus’ teachings as recorded in Matthew and the other Gospels were among the latest canonical works to be produced by the early Church. So these teachings should be intended by the scriptural authors as relevant for the long-term wait for Christ’s return at the end of the age.

Response to (2):

(a) Perhaps we should fight the cultural trend of depersonalization and establish communities of our own in which to live out these personal ethics. Perhaps we should not concern ourselves with larger social, global problems—or perhaps we should not approach such problems from a large perspective. Perhaps we should not let the ethics of complex organization override the ethics of interpersonal relationships.

(b) Jesus did confront some institutional figures in his lifetime: the Temple, the Sanhedrin, Herod, Pilate (and not just during Passion week!).

Responses to (3):

This is a tough one. Should we remain a powerless witnessing minority, and shun power when it is offered to us? Or should we be distinctively different when in power? If Jesus teaches us to love our enemies, what will this mean for a Christian who is elected as commander in chief of the United States armed forces?

Response to (4):

The gospel in both testaments clearly (as it seems to me) involves a call to those who have accepted grace to live out God’s law, and the commandments of Christ—a call that we are expected to fulfill, not to perpetually fall short of.

How to see Jesus’ journey toward the cross: as both political and spiritual, only spiritual, only political, or something that defies the distinction of political and spiritual?—this is a challenge for me.

Reflection #2

Consequences for our Christianity:

Either Jesus (and more broadly the New Testament revelation) introduces into our lives a distinctive ethic, or else it does not. Where does either option leave us, as Christians?

Suppose we are forced to look to natural revelation for our ethics.

“Is there such a thing as a Christian ethic at all? If there be no specifically Christian ethic but only natural human ethics as held to by Christians among others, does this thoroughgoing abandon of particular substance apply to ethical truth only? Why not to all other truth as well?

…what becomes of the meaning of incarnation if Jesus is not normative man? If he is a man but not normative, is this not the ancient ebionitic heresy? If he be somehow authoritative but not in his humanness, is this not a new gnosticism?”(22)

Suppose Jesus does call us to a distinctive set of ethical standards.

Must we all then turn our lives upside-down?

------

"He Himself is our Peace." (Eph 2)

Sunday, November 11, 2007

The Politics of Jesus and the disciple's cross

Now Reading:

The Politics of Jesus, by John Howard Yoder

I have gotten about 40 to 50% of the way through the book by now. For those who don't know, John Howard Yoder was a Mennonite theologian who taught at Notre Dame and the Mennonite seminary in Elkhart and wrote many books during his academic career. One of his noted students is Stanley Hauweras. Yoder himself was a student of Karl Barth at the University of Basel.

The Politics of Jesus is perhaps Yoder's best known book; he published it in the early seventies.

I liked the first chapter very much, for a beginning. He is good at articulating the positions and arguments of others. In the first chapter of Politics of Jesus, Yoder lists off a number of different arguments mid and late twentieth-century Christians have given for why the life and teachings of Jesus are not of immediate practical, political relevance. Yoder also clearly distinguishes his own project from the then-popular notion of Jesus as a generic political revolutionary to whom one can appeal in support of whatever radical political views one wishes, and from a "WWJD" model of moral discipleship, which looks elsewhere (e.g., natural law) for one's ideas of what right conduct is, but uses Jesus as a motivator for doing the right thing no matter how unpopular or inconvenient it might be. Yoder is interested in drawing a concrete, socio-political Christian ethic out of the teachings of Jesus--and he argues for continuity of such an ethic across the teachings of the New Testament writings.

In the next couple of chapters he quickly outlines the message of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke in broad strokes, and connects it to the restoration of the Jubilee year in the Hebrew Law. (Every seventh year, Israelites were to (a) not farm their land and trust to God to provide for their needs by an abundant crop the sixth year, (b) release all indentured servants/Hebrew slaves, forgiving their debts, and (c) restore the former slaves to their ancestral land which they received under Joshua in the original conquest. Yoder argues that Jesus' gospel was in essence a declaration that God wanted His people to put the Jubilee year into practice as a community, with all of its economic implications, together with even more radical injunctions such as loving one's enemies. That the Jews were not in a position of political dominance in Judea and Galilee was irrelevant, as God's people are to trust Him to take care of military and political victories--not to fight for themselves as the militant Zealots wished to--and simply obey the word of the Lord.

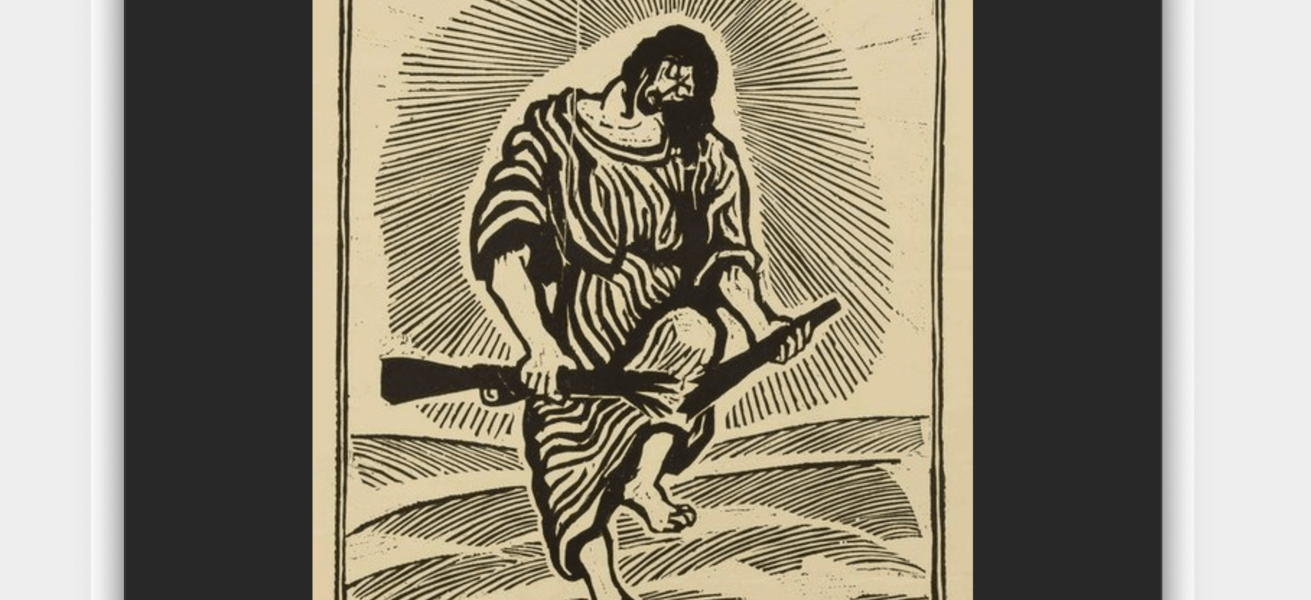

Yoder goes on to characterize Jesus' life and message as essentially a rejection both of quietism or withdrawl from the political arena (Christianity a pure, apolitical religious movement) and the violent, military revolutionary methods of the Zealots. Jesus fearlessly preached a politically charged message, was recognized by both Jewish and Roman leaders as politically dangerous, while refusing to defend himself or take up a sword and fight. Jesus is repeatedly tempted to take the easier road to kingship by the use of the sword and repeatedly rejects it in favor of the inevitable suffering of the political execution that awaited him at the end of his ministry. He told his disciples likewise to reject lordship and to reject violence, and to "take up your cross and follow" him on the road of carrying this particular nonviolent political message and being executed for it by the armed political authorities.

Yoder's book is not focused on the atonement. He rejects an exclusively spiritual interpretation of Jesus' cross, or the cross of the disciple. But I don't think he would reject the evangelical notions of sin and atonement through the cross. But even if he does, I think his views deserve careful consideration, and could be made compatible with an evangelical view of the atonement.

Still reading and still processing...

I don't have the book with me at the moment; I might post in more detail later for anyone who might be interested.

------

"He Himself is our Peace." (Eph 2)

Friday, November 2, 2007

Minor (but repetitive!) citation issue

Does anyone know the answer to this question (and could you provide a reference to confirm it)?

When one is making a bibliographic entry for a book published by Oxford University Press / Clarendon Press, (1) when does it matter, if ever, that one specify "Clarendon Press" or "Oxford University Press", and (2) when, if ever, does one give "New York" or "New York and Oxford" or "Oxford and New York" as the location instead of "Oxford"? Is there any standard on this at all???

------

"He Himself is our Peace." (Eph 2)

Thursday, November 1, 2007

Minor comments on Evan Almighty...

Movie reviews aren't usually my blog post of choice. But last night we watched Evan Almighty for the first time. I thought it was overall rather stupid (but good enough to watch once). I thought that the extra features on the DVD about making the movie a "green" film were interesting (i.e., making the ark recyclable, and giving the used materials to Habitat for Humanity, and planting trees to try to decrease the overall carbon footprint of the production) ...but I really didn't think the movie itself was as much an environmental flick as the special features made it sound. (I watched those features first, before the movie, which I know is an odd thing to do.) I suppose it did provide an opportunity for some reflection on being foolish in the world's eyes in order to do what God is calling you to do / what you think is the right thing to do, morally. And it was worth a few laughs.

There was one thing (minor within the movie) that I found offensive. (Disclaimer: you might interpret this as a "liberal" comment on my part!). In once scene, God appears in the chamber where a congressional committee is convening, in the middle of their saying the pledge of allegiance (to the American flag), and he joins in. Now, to be fair, I'm sure the primary reason for doing this was just for frivolous amusement, and I suspect that any political/religious statement buried in this event is limited to a vague comment on the whole issue of the "under God" phrase being in the American pledge. (Again, I think it is most likely that they were having fun with it, and nothing more!)

But in a combined amused/irritated way, I strongly object to the portrayl of God saying the pledge of allegiance to the American flag! (OK...he didn't start talking until the "one nation under God" part, so maybe he wasn't really pledging allegiance to the American flag...). It seems so obvious (to me) that this turns any notion of dual-citizenship on its head. If Christians owe any allegiance to their nation, its flag, its ideals, its constitution, its laws, its authorities, whatever...this allegiance is unquestionably secondary to the allegiance we owe to God, Christ, and His Kingdom. God certainly does not owe any allegiance to the U.S. I *hope* that the filmmakers were not endorsing a "God is on America's side" viewpoint, but I seriously think that many nonAmericans could interpret it this way, and rightly take offense at such a viewpoint as arrogant nationalism mixed with dangerously bad theology.

I can tell that I'm ranting. So I'll stop.

:)

Oh, and happy All Saints Day, if anyone cares. If you're a saint, or knew some saints now dead, I guess it has relevance. I don't know that much about what All Saints Day is *supposed* to be about, but I personally think it makes more sense as a day for the memory of saints (any saints, in general) that have died than Memorial Day does. Not that I've been observing it as such.

Now I'm not ranting, I'm just rambling. Definitely stopping now.

------

"He Himself is our Peace." (Eph 2)